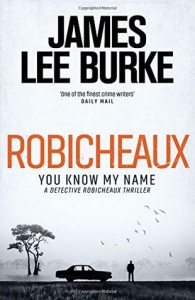

James Lee Burke

James Lee Burke

Burke kicks off Robicheaux ingeniously by placing its hero in a predicament that will horrify but grip long-term followers of the books in particular. A constant of all the novels has been Robicheaux’s struggles with alcoholism, depression and Vietnam trauma. One of Burke’s great strengths has been to gift his protagonist with very human flaws: abiding feelings of anguish, shame, self-disgust and the temptations of rage.

Robicheaux is grieving after being widowed for the third time. As his sobriety finally cracks, he finds himself back on “the dirty boogie”. “They live in me like a snake that slowly swallows its prey,” he says of his demons, “compressing it into a canister of despair and pain.” Prone to psychotic visions of the dead, he reflects that there is “no afterlife but only one life, a continuum in which all time occurs at once, like a dream inside the mind of God”. Alcohol appears to him “like an irresistible thread from an erotic dream you can’t let go of at first light”.

He wakes from an alcoholic blackout to find that he may have torn apart with his hands the man who killed his wife in a car accident. But is he being set up, and if so, why? As ever, the plot opens out to encompass a vivid cast of characters that reflect the singular culture of Louisiana, including a Robert Penn Warrenesque novelist, a charismatic local oligarch with presidential ambitions and a seedy white supremacist. Also in place are Burke’s masterly command of natural description, that gaudy, rambunctious dialogue and his hero’s lyrical meditations on virtue and corruption, shot through with a kind of personal liberation theology.